ROSE ENGINE LATHE

History

Guilloché, as we know it in horology, emerged in the 18th century with the advent of the first machines: linear engraving machines and rose engine lathes. Both are used to engrave a repeating pattern (linear for the linear machine and circular for the rose engine lathe). Guilloché appeared during the peak of the enamelling art, and the two crafts were often combined to create flinqué decorations adorning jewellery boxes, snuff boxes, and, of course, watch cases and dials.

Description and Operation

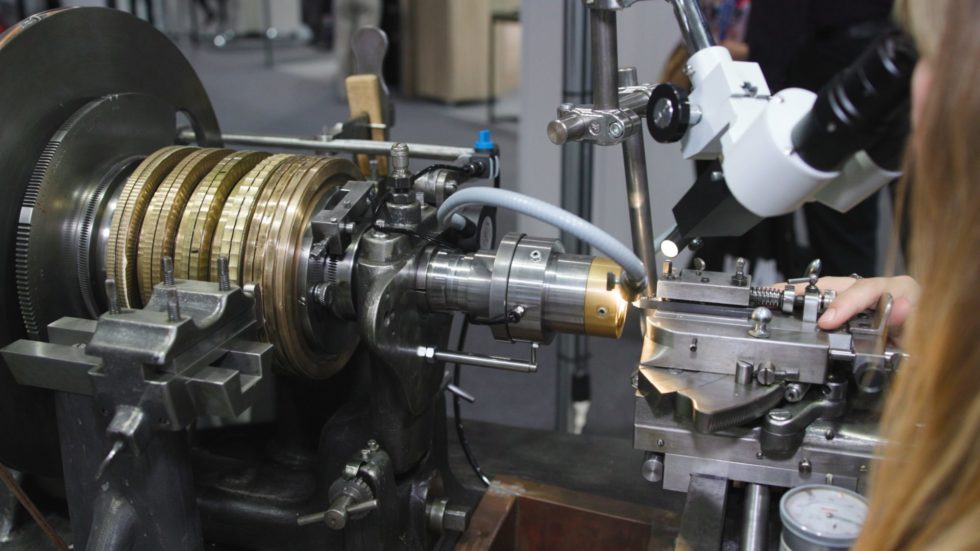

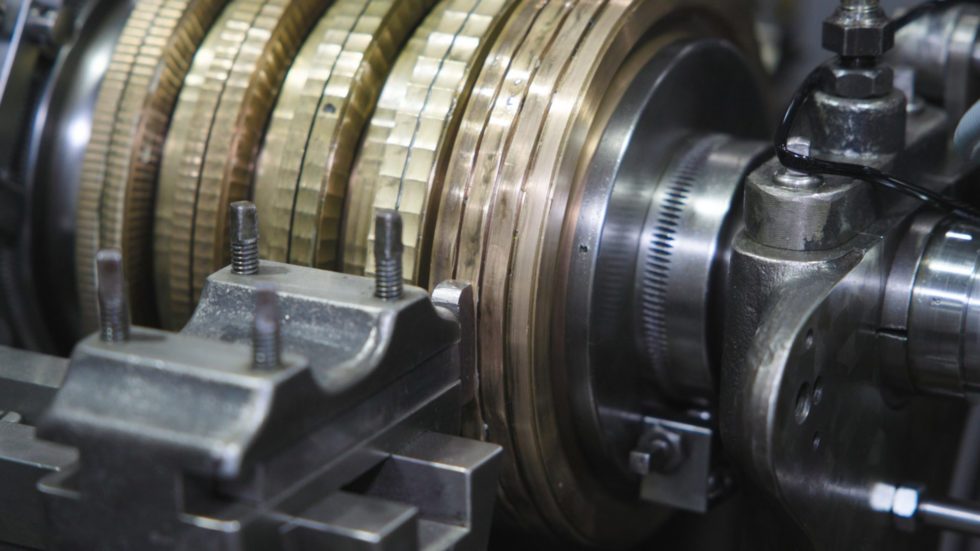

The rose engine lathe is a manually operated engraving machine used by the guillocheur (rose engine turner). By turning a pulley or a toothed wheel with a crank or pedal, the guillocheur sets into a rotational motion the platform, on which the object to be engraved is securely centred. Controlling the exact rotation speed is crucial to ensuring a consistent and lustrous groove. The artisan’s other hand pushes the carriage that holds the graver, managing its pressure on the material. As the piece to be engraved rotates, the carriage, equipped with a lever that is kept in contact with cams chosen and adjusted on a shaft by the master, dictates the engraving pattern. The movement of the lever, in contact with the cams, causes the carriage—and thus the graver—to move while the piece rotates. The machine’s mechanism synchronises the camshaft speed with that of the platform holding the piece.

Although the rose engine lathe is technically a machine, the engraving process described here is a manual craft requiring great skill and experience. Similar to hand engraving, the shape of the graver affects the visual result of the decoration. V-shaped gravers with specific angles may be chosen, as well as rounded ones. The gravers are selected and shaped according to the specific design to be guillochéed. In addition to defining the pattern, the cams can adjust the spacing between each groove, which can be regular or graduated, depending on the desired effect. The countless combinations of cams and variations in groove spacing provide an infinite array of decorative possibilities that continue to be explored and developed today.

Materials

Most metals, as well as mother-of-pearl, can be worked on the rose engine lathe. Although, malleable metals with a lustrous finish are preferred. Silver and gold are thus the most favoured materials.

Today, some rose engine lathes are motorised, meaning it is no longer appropriate to refer to this as hand guilloché. Additionally, motifs resembling rose engine turning can now be achieved through milling or stamping, but the shine of a groove created by hand guilloché is incomparable. These latter techniques are often mistakenly referred to as guilloché.

While the craft of guilloché is experiencing a renaissance and seems to be firmly re-established, no new rose engine lathes are being manufactured today.